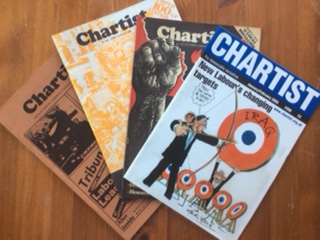

Chartist has been in production for 50 years. As a publication it is one of the longest running left Labour periodicals. Initially a monthly, and since the late 1970s a bi-monthly, the journal has sought to provide a vehicle for the critical socialist left. While not being formally a party publication, Chartist has always been oriented towards the Labour Party and largely, though not exclusively, written by Labour Party members. Patricia d’Ardenne spoke to the editor, Mike Davis, to get a view of the magazine’s history and current outlook.

Tell us when and how you became involved with Chartist

In the summer of 1973, a group of us had been active in the International Socialists (now SWP) in north London. We had been arguing for at least a year that IS should join the Labour Party, to help develop a more socialist wing. We had noted the influence of Tony Benn and the standing that left figures in the Labour party had with the militant trade union movement – in particular, the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders’ campaign and occupation against closure in 1972. For us this indicated ‘reformism’ was not dead and that the Labour Party was not a church without a congregation (as argued by leading IS theoreticians). We had written internal papers making the case for LP membership but to no avail.

In the Spring of 1973 we were grouped with several other critical opposition trends in the IS and labelled the Right Opposition. About 100 of us were summarily expelled for refusing to stop arguing for our views.

One of us had heard of a small group of revolutionary socialists in the Labour Party called Chartists. We did not like the politics of Militant which were extremely workerist, class reductionist and sectarian. ‘Chartist’ sounded more open. Plus, we liked the idea of connecting to the unfinished democratic revolution of our 19th century forebears. We applied to our local CLPs for membership. Mine was Hackney North and Stoke Newington, and we were duly accepted. The leading lights in Chartist in 1973 were Chris Knight, Graham Bash, Keith Veness and Al Richardson. Don Flynn and I met with Knight and Bash and felt they were open to new ideas. We were particularly keen to develop greater democracy in the trade unions and promote an anti-racist, pro feminist, internationalist politics in Labour.

Describe your editorial history and policies

Chartist was initially an eight-page monthly tabloid newspaper, associated with the Socialist Charter. This group had emerged from the Tribune Group of MPs and party members in late 1968. Frustration with the lack of progressive socialist measures under the Wilson Labour government had been the main spur for this group. A kind of takeover of the paper had occurred, with the younger Trotskyist-minded activists shifting the group in a more revolutionary direction. There were always annual general meetings with impassioned debates on policies and analysis of events. The editor and editorial board were elected at these meetings. Under Chris Knight’s editorship, the paper became increasingly adventurist and ultra-left, advocating preparation for revolution. An appeal for a Joint Revolutionary Command of Revolutionary groups was made in early 1974. Contact work had been undertaken with the armed forces to develop trade union rights and a Soldier’s Charter booklet was produced and distributed at Aldershot and other garrison towns.

In reaction to this ‘insurrectionist’ politics, I was elected Editor in the spring of 1974, and have remained Editor ever since. A new Editorial Board was established with members from wider political backgrounds and we began to make a more determined effort to recruit women and black members.

By 1979 divisions within the group had deepened. At the AGM in 1980, a year after Margaret Thatcher’s Tory landslide, a split occurred. The majority saw the need to move away from forms of Leninist Trotskyism towards a more open, critical and reflective politics. The electoral defeat emphasised the need to re-examine some of our fundamental concepts and tools of analysis. Much of the left were stuck in a kind of ‘do not adjust your set, reality is at fault’ dogma. We realised we were in for a much longer haul. The majority of supporters wanted and succeeded in re-creating Chartist as a more discursive, less agitational publication, and by the nineties Chartist’s readership had extended to a wider political base. We had been moving in 1978 from a monthly tabloid to magazine format. A public bi-monthly magazine became the format for our ideas, complemented by regular discussion bulletins for subscribers.

In parallel to these developments we also made a short-lived alliance with the Worker’s Fight group to form the Socialist Campaign for Labour Victory in 1978/79. We launched a newspaper, Socialist Organiser, which I jointly edited. Ken Livingstone, Jeremy Corbyn, Ted Knight and other local government activists were involved. Sadly, our partner (now the Alliance for Workers Liberty) sought to take control of what had been a pluralist run grouping. We withdrew from the project.

The 1980s also saw Chartist linking up with the libertarian socialist Intervention Group and activists from Big Flame who had joined the Labour Party.

Chartist embraced a more ‘eclectic Marxism’ (a term coined by Yanis Varoufakis), looking at the work of Gramsci, feminist and new left writers. Local government became a major focus of the struggle against Thatcher’s policies. We produced a Chartist magazine supplement, Local Socialism, which had regular contributions from councillors and local government activists. Our pamphlet, Go Local to Survive – produced jointly with the Labour Coordinating Committee (LCC) – saw the decentralisation of power and provision, from housing to environmental services, as a key feature of the fightback against the huge funding cuts being imposed. Later the battle against rate capping and the Poll Tax became important loci of our work.

Internationalism has always been a central feature of Chartist politics. We see it as fundamental to our socialism going back to the days of Keir Hardie and a tradition that was temporarily crushed in the First World War, when social democratic and labour parties followed their own national governments into the carnage.

Ireland was also a central feature of articles in Chartist over the three latter decades of the 20th Century and also of the political activity of subscribers. Many of our supporters had been involved in the Troops Out Movement and the Anti-Internment League. We viewed the Labour Party’s position as reinforcing the oppression of Irish people and obstructive of Irish independence. We helped found the Labour Committee on Ireland and its magazine Labour and Ireland. Chartist supporters also produced Ireland Socialist Review, a more theoretical journal, over several years. We also published several pamphlets, one with an introduction by Ken Livingstone; another, in the early 1990s, being a compilation of the Chartist ‘Belfast Letters’ column written by Bill Rolston, an Irish socialist. We also became more positive about Europe, moving away from the traditional left anti-Common Market/European Economic Community equals capitalist club position, regularly publishing articles on developments in Europe.

We developed a relationship with the LCC, had EB members on the National Steering Group (which included Ken Livingstone, Michael Meacher, George Galloway, Peter Hain, Charles Clarke and many others who became key players in the Blair government). We had an arrangement that LCC bulk-purchased Chartist to distribute to its members.

In the late 1980s we linked up with Clause Four, a group of Labour students and youth, perhaps not so youthful then. Nigel Stanley, an earlier C4 activist, became the LCC secretary. He was an important figure in our editorial work, writing a regular ‘Inside Left’ column. Publicising trade union activity – particularly the miners strikes, supporting industrial action and occupations, workers’ planning and other initiatives – was also an important part of our political coverage and campaigning in the magazine. The creativity of workers up against the wall should be a constant source of inspiration for the left.

But some things have remained the same. We are still focussed on transforming Labour into a (democratic) socialist party. We supported the election of Jeremy Corbyn and most of the EB were enthusiastic about the prospects for reinvigorating Labour’s international socialist credentials.

The best route to transforming British society out of the inequities of capitalism is through the Labour party, trade unions, cooperative movement and civil society groups. For Chartist this involves supporting activists in local, regional, national and international government forums working for fundamental change. We continue to highlight the importance of race, sex, gender and other oppressed people in struggles on a par with class struggles. And we continue to promote informed internationalist politics.

Tell us about Chartist readership then?

In the 1970s Chartist was largely read by youth activists in the Labour Party. The Labour Party Young Socialists was an important focus for our work, although it was controlled by the Militant tendency. Publications were sold at CLP meetings, demonstrations, conferences. Most copies of Chartist distributed were hand sales, with few subscriptions, compared to now.

How have you influenced Labour?

Impossible to say. Pluralism, openness, a quest for new ideas and fresh thinking have animated the magazine. We largely subscribe to a bottom-up, anti-statist socialism, though that doesn’t mean we don’t work for well-funded public services and a democratically socialised economy. We have had numerous subscribers who are councillors, MPs and local activists. We’d like to think some of the ideas promoted in the magazine have translated into policies and action. We have often produced special editions of Chartist for Labour Conference. We worked with the Labour Co-ordinating Committee, producing several pamphlets. A seminal publication was New Maps for the Nineties – A Third Road Reader (edited by Neal Lawson, now involved in Compass). This helped popularise the concept of a route to democratic socialism that was neither revolutionary nor reformist, but combining a parliamentary with an extra-parliamentary road. It reflected strong elements of a libertarian socialism many readers espouse. Unfortunately, Tony Blair’s mangled version of a Third Way, influenced by Anthony Giddens, soured the concept for most of the New Labour period. So it wasn’t possible to sustain the concept during this time. We have always welcomed contributions from MPs and trade unionist activists and intellectuals.

As for the future?

It’s impossible to predict the future, but I’d like to think the world could be saved from ecological extinction or the threat of barbarism, neo-fascism or totalitarianism with a more enlightened democratic socialist world. Prospects don’t look great right now, but the green movement, the continuing vibrancy of feminism and the passion for democracy in many countries across the world suggest that things could be different.

In the future, Chartist might be an underground-type publication, something produced in a digital/hologram format accessed simply by pressing a button on a watch. But we’ll maintain print and digital production for the foreseeable future.

Something like Chartist advocating an end to exploitative capitalism, class, gender, racial and other inequalities should be necessary until the creative potential of all human beings is realised and our species learns to live in harmony with itself and the natural world of which we are part.

Any interest in an article ‘The Cooperative Road to Socialism’, linking the present Cooperative movement to essential change?

How many words would you want

Regards